Who could have believed that the world was flat? Or that it sits fixed in space, while the cosmos revolves around it? Anyone with two eyes, that’s who. It takes a leap of imagination to contemplate the alternative — that we are standing atop a rapidly spinning sphere, hurtling through space.

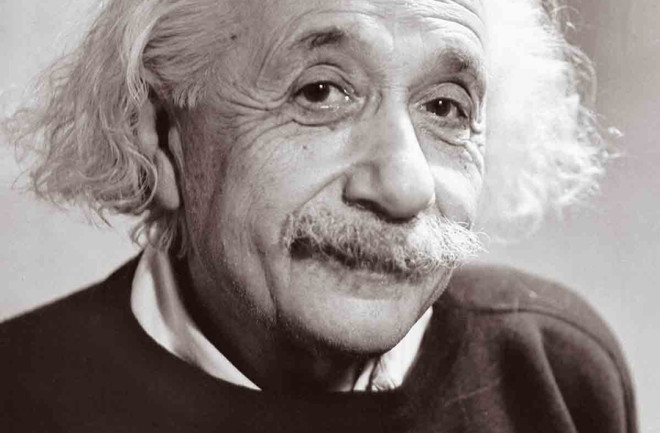

Albert Einstein, like Nicolaus Copernicus and Galileo Galilei before him, redefined our understanding of the universe, and he did so thanks to a knack for keeping his thoughts clear of unnecessary information. In fact, he conducted experiments on the basis of thought alone, playing them out in something like the construct from The Matrix — a completely empty space populated with only items essential to his experiments. A clock. A train. A beam of light. An observer or two. An elevator. “Imagine a large portion of empty space, so far removed from stars and other appreciable masses,” said Einstein, describing his mental construct.

Using these ingredients, plus some basic physical principles, Einstein came to mind-boggling yet unavoidable conclusions that overturned all of physics. With special relativity, he showed that time and space are intertwined, not demarcated by the same gridlines and tick-tock regularity for everyone. A decade later with general relativity, he found that gravity actually distorts space and time.

It all started when, at the young age of 16, Einstein conjured up a vivid thought: What would it be like to race alongside a beam of light? The idea seems innocuous enough; if I race alongside a motorist on the freeway and match its speed, we come to a relative standstill. I could say that it is the outside scenery scrolling backward past us, as if we were playing an arcade racing game. Einstein wondered if the same would hold true for the light beam. If he drove fast enough, could he pull neck and neck with the beam, bringing it to a virtual halt? What would the world look like to such a light-speed traveler?

It was Einstein’s imagination that allowed him to take leaps and make connections that his contemporaries could not. He explained his insights by analogy: “When a blind beetle crawls over the surface of a curved branch, it doesn’t notice that the track it has covered is indeed curved. I was lucky enough to notice what the beetle didn’t notice.”